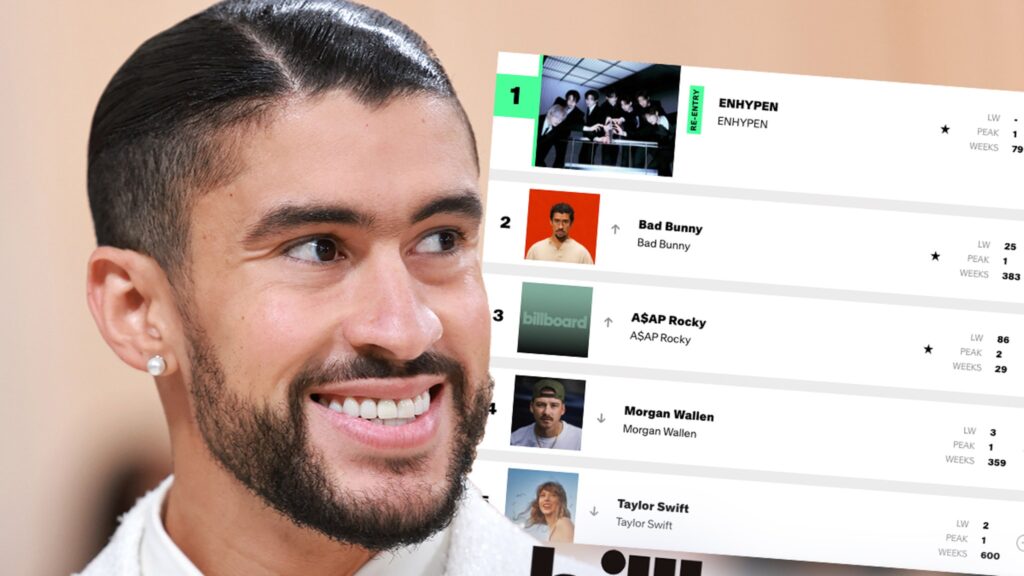

A ROAD. That, to Chameli Bhandari’s mind, was non-negotiable when she came as a bride three years ago to Sonpur, a village in Narayanpur district of Chhattisgarh’s Bastar region. Sitting outside her house, metres away from where the state highway is a blur of bitumen in the afternoon heat, Chameli, the village pradhan, says, “Had it not been for this road, I would not have married him.” Behind Chameli, her husband Paras Bhandari, a farmer, stands holding their newborn daughter. As others around her laugh, she does too, before saying, “Sach bata rahi hoon (It’s the truth).

Sonpur is in Abujhmad, the once-impenetrable fortress of the Maoist movement that’s spread across parts of Narayanpur, Bijapur and Dantewada districts of the state. Long marred by cycles of violence as its people were caught in a seemingly endless battle between the Maoists and the security forces, the region stood still.

But with a string of setbacks leaving the Maoists at their weakest, Abujhmad and the rest of Bastar are slowly opening up. With that, road projects under the special package of the Ministry of Road Transport and Highways have gained pace, and deadlines and timelines are being advanced to align them with Union Home Minister Amit Shah’s stated target of eliminating the movement by March 2026.

The 78-km Narayanpur-Sonpur-Moroda state highway, for instance, was sanctioned in 2010 and was to be completed in three years. A decade after work began, only 36 km of the road was built. But the momentum picked up in 2024 and now, the government hopes to seize on the tentative peace and push through with the rest of the work in the next few months.

All along the Narayanpur-Moroda state highway, heavy rollers are transported on flatbed trailers and convoys of trucks make multiple rounds laden with cement, iron rods and ballast. (Express Photo by Chitral Khambhati)

All along the Narayanpur-Moroda state highway, heavy rollers are transported on flatbed trailers and convoys of trucks make multiple rounds laden with cement, iron rods and ballast. (Express Photo by Chitral Khambhati)

The highways cut through areas that were until recently no-go zones for the State. Here, the road is a tactic, an ally in the State’s fight against Naxals.

A senior PWD official explains, “Road projects are not only for connectivity, but to push the Naxals deeper into the forest. Every inch of the road has to be pushed through, reclaimed by force. What happens is that security personnel or Road Opening Parties arrive in the region and put up a camp. This is where encounters and killings have happened in the past. If the forces are successful in fighting back the Naxals, the area is cleared and road construction starts. This is why we have had to divide the project into multiple packages and complete it in a phased manner.”

The Indian Express travelled 254 km along three state highways – Narayanpur-Sonpur-Moroda, Bijapur-Avapalli-Basaguda-Jagargunda and Dornapal-Chintalnar-Jagargunda – that are among the last pending road projects in the Bastar region. The highways and the smaller village roads eventually meet with the trunk route of National Highway 30 that runs down from Sitarganj in Uttarakhand to Vijayawada in Andhra Pradesh.

Story continues below this ad

In these parts, where the iron in the soil lends it a deep shade of red, the road is more than a strip of bitumen. It’s often a transaction – if it offers unimaginable opportunities in the form of schools, banks, hospitals and markets, it also takes away a way of life.

Narayanpur-Sonpur-Moroda

The clang of hammer meeting steel echoes through the dense sal forests. All along the Narayanpur-Moroda state highway that’s being built by the state Public Works Department (PWD), heavy rollers are transported on flatbed trailers and convoys of trucks make multiple rounds laden with cement, iron rods and ballast.

At the 38th kilometre from Narayanpur, Isha Parihar flings a pan full of red soil into the air over a gravel road. She is among the hundreds of workers on whose shoulders – and lives – the road projects rest.

Isha, 20, from the nearby Maspur village, earns Rs 300 a day. She isn’t sure how the road will change her life or that of the other Halbi tribals in the area. “Maybe we will get schools,” she says, before returning to work. Isha lost her parents at an early age and dropped out after Class 8.

Story continues below this ad

Chameli Bhandari, sarpanch of Sonpur, says she wouldn’t have married her husband if the village didn’t have a road. (Express Photo by Chitral Khambhati)

Chameli Bhandari, sarpanch of Sonpur, says she wouldn’t have married her husband if the village didn’t have a road. (Express Photo by Chitral Khambhati)

PWD officials said the security threat in the region had prompted them to divide the 78-km road into 44 packages, with work awarded to multiple contractors. They are now targeting a completion date of March 2026.

Electricity poles, connected by neatly aligned wires, run along the seven-metre-wide highway. So does a water pipeline under the Centre’s flagship Jal Jeevan Mission. At least 10 CRPF and BSF camps appear intermittently along the route, providing protection to the road construction workers.

Guddu Ramnureti sits on his haunches under a tendu tree at the intersection of two roads that are under construction – the state highway and a 16.3-km-long road under the Pradhan Mantri Gram Sadak Yojana emerging from it. His village, Tarobeda, is 3 km away. He is waiting with a group of villagers for a vehicle that will load their forest produce and take them to Narayanpur market, 40 km away.

“Until last year, there was no electricity in the village. The road is still being built, but vehicles, most importantly ambulances, have already started coming. Earlier, if someone fell sick, we had to carry the patient on our shoulders for 40 km to the government district hospital in Narayanpur,” says Ramnureti.

Story continues below this ad

A few kilometres ahead, clear water trickles through the narrow channel of the Kundala river that crosses the highway alignment at multiple points. A convoy of armed BSF personnel on Royal Enfield Himalayan motorbikes periodically veers off-road, only to reappear moments later. They are returning after an operation deep in the forest to their camps along the highway.

Further down, Aayturam Usaindi talks of his “dream” that’s slowly taking shape. Along with his two brothers, he is building a three-room house, with a small verandah, in Beril Tola of Putwada village with the Rs 1.20 lakh they got under the Centre’s flagship housing scheme, the Pradhanmantri Gramin Awas Yojana (PMGAY).

Aayturam Usaindi and his brothers are building a three-room house in Putwada village. (Express Photo by Chitral Khambhati)

Aayturam Usaindi and his brothers are building a three-room house in Putwada village. (Express Photo by Chitral Khambhati)

“They (Naxals) would not allow us to take any government benefit. Woh bolte the ki sadak nahi banane dena hai, puliya nahi banana hai (They would say, we won’t let them build roads, bridges). Because there were no roads, we could not build homes. But now, a Bolero can come directly to our doorstep. The biggest relief is that we can reach the hospital easily,” says Usaindi, 35.

He hopes the road will change lives for others in the village too. The village does not have electricity lines; the water pipeline that was laid last year is still dry; and the Ujjwala scheme hasn’t touched these parts. The village primary school is a one-room structure with 17 children on the rolls. Today, there were just four girls, sitting on the floor, facing the blackboard where a scrawl in chalk read: “Lakshya Ek – Bastar Shrestha (One goal: The Best Bastar)”.

Story continues below this ad

“We have spoiled our lives by not getting an education. If I can provide good education to my children, it will be good for everyone,” says Usaindi.

Despite the optimism, there’s something that bothers Usaindi. “Naxali chale gaye. Ab toh jangal kaate ja rahe hain, unko mana karne wala koi nahi hai (The Naxals have gone. Now the forests are being cut, and there is no one to stop them),” he says in a mix of Gondi and Hindi.

As the road continues deeper inside, it becomes almost still – there are few faces and fewer houses. A few metres beyond the Satdhaar river that cuts across the road alignment, Maoists have put up their own gate. This is a no-go zone. Our mobile phone signal drops.

It’s now late afternoon. On the way back to Narayanpur, the road near Kandulnaar village, which was deserted until a few hours ago, suddenly springs to life. It is the weekly market. Under blue, yellow, and green tarpaulin sheets, people sell everything from clothes and food to utensils and masalas.

Story continues below this ad

“The road was always here. It was a 3-metre-wide carriageway. But when the Maoists came, vehicles stopped coming this way. It gradually turned into a small pathway with a lot of deep potholes. Once this road widening project is complete, people from far-off villages will be able to come here and the economic activity in these parts will go up,” says a PWD official.

The highways cut through areas that were until recently no-go zones for the State. (Express Photo by Chitral Khambhati)

The highways cut through areas that were until recently no-go zones for the State. (Express Photo by Chitral Khambhati)

At pradhan Chameli Bhandari’s house, her husband Paras Bhandari, who says he came close to getting a police job but declined the offer for fear of the Maoists, talks about the change in “mahaul (atmosphere)”. He uses a one-room house in the village to make his point. “See that house? The roof is an asbestos sheet, but there is a line of khaprail (mud tiles) at the top to prevent rainwater from seeping in. This asbestos sheet is the kranti (revolution) that has happened here; the khaprail is the past. Earlier, the Naxals wouldn’t allow us to build such houses,” says Bhandari, who belongs to the Halbi tribal group.

Metres away is Dhirendra Mishra’s ayurveda dispensary. Three years ago, his dispensary, which he has run since 2003, was converted to an Ayushman Arogya mandir under a Central government scheme. “This highway was earlier just a trail. There were so many drains on the way that we had to get off our bikes midway, cross the drains in our underwear, and then get dressed again. It took about 2.5 hours to travel the 26 kilometers from Narayanpur to Sonpur. Now even cars come to our village,” says Mishra, adding that the Naxals never threatened him.

“Of course, there was fear — they had weapons. They would decide on which days I could come to the clinic. Not even a chilly could be sold in the market without their permission. They sat in judgment on everything,” says the doctor. But that changed, he says, once the road came.

Road to Bijapur

Story continues below this ad

After almost 180 km and a 4.5-hour ride from Narayanpur, past the Indravati river, a gate welcomes travellers to the 70-km Bijapur-Avapalli-Basaguda-Jagargunda road. On its tiled walls are names, birth and death dates, and illustrated sketches of dozens of CRPF personnel killed during the construction of the road between 2010 and 2022. The gate was put up when the state highway was completed in December 2025.

Minutes into this highway, men on two bikes shout out, “Do not go more than five metres beyond the roadside; it’s not safe.” They are personnel of the CRPF and the state police. They take photographs, note down details, and record how far we will travel on the highway.

“There could be IEDs planted along the roadside. We have lost many of our men,” warns one of the CRPF personnel before letting us proceed. A long stretch of upturned mud on both sides of the highway bears out that warning – wires connected to IEDs planted in the area were dug out from here during past searches.

This state highway was sanctioned in December 2010. However, the company which first won the bid could complete only 43.5 km of the total 70 km. After this, a series of disruptions forced the company to abandon its work. Hyderabad-based Keystone Infra Private Limited, which won the bid in 2020, then completed the remaining 23.5-km stretch.

Story continues below this ad

At the start of the 70-km Bijapur-Avapalli-Basaguda-Jagargunda road is a gate with names and sketches of CRPF personnel killed during the road construction. (Express Photo by Chitral Khambhati)

At the start of the 70-km Bijapur-Avapalli-Basaguda-Jagargunda road is a gate with names and sketches of CRPF personnel killed during the road construction. (Express Photo by Chitral Khambhati)

Mohammed Nayeemuddin, the company’s project manager, says the challenges were enormous. Nayeemuddin would start his morning by writing letters to the Superintendents of Police in Bijapur and Sukma, asking for the deployment of security forces at the project site. It was one such Road Opening Party (ROP) that came under attack on April 4, 2021 – 22 CRPF security personnel and at least four Maoists were killed near Tarrem village.

“We cannot imagine going to the project site without ROP. On paper, we are allowed to work 18 hours a day, but due to the security situation, we can only manage 5-6 hours, that too on an average of four days a week. Another challenge is that the locals are too scared to work. So I have to get people from other states. I have 170 employees from the company and 120 daily wagers from Bihar, Bengal and Jharkhand,” says Nayeemuddin, pointing to a culvert on the highway that was blown up by the Maoists.

“After the attack, work was completely stopped for two years. We resumed work in 2024 and had to complete whatever we could,” says an official from the construction company.

A smooth blacktop road, marked freshly with white stripes, starts appearing from Tarrem village. The village got a large helipad before anything else. Its biggest building is the police station — a newly whitewashed fortress fenced by concertina wires that’s a reminder of the fragility of peace. In Tarrem, a small bank is under construction, a kirana store has started to run out of one of the shops built under the District Mineral Fund (DMF) and the village panchayat bhawan is being renovated.

Ramdas Aulam, 27, returned to Tarrem a few years ago. His family was forced to flee to Bijapur to escape the harassment at the hands of the Salwa Judum, an armed civilian vigilante group set up by the State.

“Uss samay ek ajeeb hi mahaul tha (Those were strange times). People would kill anyone they caught hold of. All that has changed, but the biggest change has been this road. Now we get ration easily and we can run to Basaguda or Bijapur when we fall ill,” says Aulam, a Biology graduate from Bastar University who is without a job. But the government needs to do more than laying a road, he says.

The road glows in the afternoon sun as it reaches the Jagargunda T-point in Sukma. (Express Photo by Chitral Khambhati)

The road glows in the afternoon sun as it reaches the Jagargunda T-point in Sukma. (Express Photo by Chitral Khambhati)

“Villagers find it difficult to work under MGNREGA because payments are made through banks, and there is no bank or ATM nearby to withdraw money.”

Like elsewhere, there is a hint of worry about what lies ahead. “When the Naxals were here, they protected jal, jungle, zameen (water, forest, land). Now, as they are being eliminated, trees will be cut on Adivasi lands and minerals will be extracted at will. Recently, there were reports of trees being felled in Bijapur. Officials carry out the work the way they please and we are pushed to the margins,” he says.

Korsa Sundar knows what it is to be pushed. Stepping out of his one-room kutcha house at Silger village in Bijapur district, he walks up to the road that is within touching distance and marks a line where the road ends. “It should not extend beyond two lanes. From here, our land starts. If there is land, children will survive; if there is no land, our children will die. Isn’t that right, sir? The Naxals have run away from here, now the government should listen to us,” says Sundar.

A senior CRPF official sits at a newly built camp down the highway. Behind him hangs a large map of Bastar region, with stars in nine colours to indicate camps of various battalions. “We cannot say Maoism has ended, but we are at the elimination stage. We set up camps and with that came electricity, optical fibres for the internet… We are getting a lot of support from the locals. They feel that things have changed and they are ready to change,” he says.

The road glows in the afternoon sun as it reaches the Jagargunda T-point in Sukma. Here, Nayeemuddin is filled with pride as he looks back at the road, a gleaming ribbon of black. Tapping a PWD engineer on the shoulder, he says, “Dekho ab kaisa lag raha hai. Kar hi dikhaya (See how beautiful it looks. We finally did this).”

Road to Sukma

The cement-concrete highway from Jagargunda to Dornapal, around 36 km before Sukma city, is a spur of NH-30. Being built by the state’s Police Housing Corporation, of the 20 packages for the 58-km highway project,16 have been completed.

A drive down this highway reveals similar scars: culverts blown up and an earthmover charred and frozen in time. Workers talk of engineers being threatened and contractors replaced several times over. But the worst of what this highway witnessed was on April 24, 2017, when 25 CRPF personnel were killed after being ambushed by almost 300 Naxals.

The Bijapur-Avapalli-Basaguda-Jagargunda state highway was completed in December 2025. (Express Photo by Chitral Khambhati)

The Bijapur-Avapalli-Basaguda-Jagargunda state highway was completed in December 2025. (Express Photo by Chitral Khambhati)

The first major market on the highway is at Chintalnar village. Sitting inside a kirana store, the owner, a woman in her 50s from Siwan, Bihar, says she has been here for the last 20 years. Her shop was further ahead, near where the road is being expanded for the highway. “I was asked to move here when they started work on the road. A lot has already changed. More people will come to the region. It’s good for our business,” she says. Like hers, most of the shops in the market are run by people from other states.

Back to school

On the side of the highway in Bijapur’s Silger village stands a single-storey, freshly painted primary school. The school came up recently, the first in the village. Built under a special package for tribals, it has 35 students and over a dozen rooms.

Barse Budhra, 22, is one of the two teachers who were recently appointed. He is from Puvarti, the village of Maoist commander Hidma, who was recently killed. He says the first casualty of the Maoist dominance was education. “Even when I fled my village to study in Sukma city, the police used to target me, saying I was a Naxal,” says Budhra, who is also studying for a BSc degree.

At a newly built school in Silger village, Bijapur. It’s the first school to come up in the village. (Express Photo by Chitral Khambhati)

At a newly built school in Silger village, Bijapur. It’s the first school to come up in the village. (Express Photo by Chitral Khambhati)

Just then, Korsa Savita, a Class 2 student, runs into the classroom. Others follow after the mid-day meal and take their places behind the desks. How many of them want to grow up to become a doctor, the teacher asks, and most of the students raise their hands. Savita is the most enthusiastic, looking around the class and smiling, her hand still raised. Fewer hands go up for the other options – engineer, pilot, teacher. Police, CRPF? No hands go up. Savita’s smile vanishes.

Outside the classroom window, the road stretches on. As the sun falls on the dug-up earth, it’s a new shade of red. A new Red Corridor.